Illustration: Filip Fröhlich

What stands out the most to you when you’re listening to a song?

For the average listener, it might be the melody, lyrics, production, or how it makes them feel—most people’s answer probably wouldn’t include vocal harmonies. We don’t typically pay much attention to them, but the truth is, we would certainly miss them if they weren’t there.

Vocal harmonies can make or break a song. They have the power to take it from an amateur-sounding bedroom recording to a radio-ready hit. They help create captivating live shows and breathe life into songs performed by choirs and acapella groups.

Despite their crucial role in music, it’s common for singers to treat them as an afterthought—something they throw in hastily at the last minute.

If you’re a singer, recording artist, or producer who works with artists, take the time to master vocal harmonies. Use them with intention and take full advantage of what they can add to your music. You’ll almost immediately see a noticeable difference in the overall quality of your songs and performances.

If you don’t know how to find vocal harmonies or can’t do it reliably for any song, then this guide is for you. We’re breaking the process down and showing you step-by-step how to write your own harmony lines and how to choose notes that sound great together.

Feel free to use the table of contents below to quickly navigate to a specific section.

What you’ll learn:

- What is a vocal harmony?

- The music theory behind vocal harmonies

- Understanding chords and melodies

- How to create vocal harmonies in five steps

- How to harmonize: Follow along with an example

- Other types of vocal harmonies

- Trust your ear

- How to practice vocal harmonies

Ready to take your songs to the next level? Let’s start harmonizing!

Voice to verse—anywhere. With the addition of Splice Mic, you can instantly test and record ideas, explore genres, and unlock new creative possibilities, all from the Splice mobile app.

What are vocal harmonies?

Vocal harmonies are any vocal lines sung simultaneously with the melody. They don’t repeat the melody exactly, but rather complement it. They follow the same rhythm and fit over the same chords, but their notes are different.

While a song can only have one main melody, it can have any number of harmonies. They help add weight and texture to the vocal and reinforce the underlying chords. They’re often used to highlight important parts of the song, add depth and movement, or create a sense of tension and release.

The music theory behind vocal harmonies

Coming up with vocal harmonies is both a science and an art—it requires knowing a bit of music theory, but also relying on your ear. We’ll be just scratching the surface here, but to help make sense of the theory part, let’s go over a few basics.

And if you’re already familiar with scales, intervals, and chords, feel free to skip this section.

Keys and scales

When making music, we have 12 pitches available to us. We don’t typically use all 12 in a single song, though, because without intention, that would have no harmonic structure and sound too messy. Instead, we choose a set of seven pitches and, for the most part, center each song around it. This set is called a key.

When we line up the seven pitches of any given key in an ascending or descending order, we make a scale. One of the easiest keys to understand is C major. Its scale consists of all white keys on the piano: C, D, E, F, G, A, and B.

Intervals

Intervals measure the distance between any two notes, and they’re the building blocks of scales, chords, and melodies. We talk about smaller intervals in terms of half steps (semitones) and whole steps, but for larger intervals, it’s easier to measure them based on the notes in the scale. Let’s keep using the C major scale as an example.

Going from C to E takes us three notes—C, D, E—so we call that interval a third. The distance between C and G would be called a fifth. Going from C to the next C takes eight scale notes, so we call that an octave.

There’s a lot more to learn about intervals, but for now, all we need to know is that, when it comes to playing two notes at the same time, certain intervals sound more consonant than others. For example, thirds and fifths sound naturally pleasing to the ear, while a second interval often sounds a bit more dissonant or tense.

Chords

Speaking of third and fifth intervals, that’s exactly how most chords are built. For example, the notes C-E-G in the C major scale make the C major chord. The notes F-A-C make the F major chord. You can use this as a starting point and make adjustments to create more complex chords and chord extensions.

We go over keys, scales, and intervals in more depth in the guide above

Understanding chords and melodies

Great vocal harmonies do two things: they reinforce the chords and complement the melody. Let’s take a look at why both are important and how to find the right balance between the two.

The role of chords in finding vocal harmonies

By definition, harmony in music happens whenever two or more notes are played at the same time. If you’re accompanied by an instrument or a track, there is already harmony happening in the chords. Any new harmony you introduce needs to match that.

That’s why, when coming up with a harmony, the first thing you need to do is look at the chord being played at that moment in the song.

Of course, this is a rule you can sometimes break, but only if you have the freedom to change the chords as you go and make them more complex than they originally were. For example, maybe you’re arranging for an acapella group or re-harmonizing a song (giving it a different chord progression while keeping the melody the same).

If that’s the case, you can freely experiment with notes that wouldn’t otherwise work with the original chords. As long as you give them context that justifies your choices, you can end up with some very interesting arrangements.

Finding vocal harmonies that complement the melody

If you’ve ever looked into how to sing harmonies in the past, you may have been told something like, “Oh, just sing the melody but shift it up or down by a third interval.”

On one hand, this is good advice. Parallel harmonies—ones that match what the melody is doing—generally sound very pleasing to the ear.

On the other hand, it only works sometimes. If, when trying to match the shape of the melody, you run into notes that clash with the chord underneath, your harmony can sound very ‘wrong.’

Does this mean that every note in the harmony needs to be a chord tone—i.e. a note that can also be found in the chord?

Not at all. In fact, when we look at melodies, they, too, are made up of a combination of notes—some belong in the supporting chord, and others don’t. Otherwise, melodies would get very boring very quickly.

So, if you’re considering singing a harmony with a note that’s not a chord tone, it may or may not sound fine. How is that possible?

It all has to do with the fact that notes can take on different roles in melodies, and these roles extend to their respective harmony lines.

Some notes act like “anchors.” They’re chord tones, and because of this, they’re typically played together with the chord, held longer, and carry more weight. They give us lots of harmonic information and help the melody make sense with the chords.

Other notes happen in between these anchors. We pass them briefly, usually on the way to another anchor note. If we gave them the same level of importance in the melody, they might sound off. But, because they don’t carry the same weight, they simply make the melody more interesting without interfering with the overall harmony.

So, here’s the general rule of thumb:

- When you’re harmonizing anchor notes, you should use other chord tones to make sure the harmony fits the chords.

- When you’re filling spaces in between anchor notes, you can harmonize the melody and more or less match its shape, without worrying about it clashing with the chords.

The only tricky part is, there isn’t always a foolproof way to identify whether a note functions as an anchor or a filler. This is where you simply need to rely on your ears and go with what feels right.

If all this makes your head spin, don’t worry. We’ll go through an example in just a moment and see how it plays out in practice.

How to create vocal harmonies in five steps

The goal is to find a harmony that fits the chords but also complements the melody.

To do this, start by identifying the key that the song is in. In the place where you want to add a harmony, identify the chords and notes of the melody. Split your melody into sections, where each section is supported by a different chord.

For each section, follow the steps below:

- Find an “anchor” note in the melody. It should be a chord tone.

- Shift your anchor note up or down so it matches a different chord tone—one that’s not already taken up by the melody.

- Shift the other notes (filler notes) so they roughly match the shape of the original melody, while staying within the same scale. More often than not, they can be shifted by the same interval as the anchor note, though this isn’t always the case.

- Test your new harmony line. Its anchor notes should match the chord, while its filler notes should complement the melody without clashing with the chord underneath.

- If any filler notes still sound off, you can try shifting them to the nearest chord tone.

How to harmonize: Follow along with an example

Let’s follow these steps together and create a couple of harmonies for the first line of “Let It Be” by The Beatles.

The song is in C major, so that’s the scale we’ll use. There are two chords supporting this line, so we’ll split it into two sections.

Finding anchor notes and outlining filler notes (“when I find myself in”)

The first section is supported by the C major chord, which is made up of C, E, and G. The melody follows the notes G-G-G-G-A-E.

We can tell that the G is an anchor note—it’s a chord tone, it lines up with the start of the chord, and feels important.

To create a harmony to this line, we look to see if there are other chord tones in the C major chord that this G can “shift” to. How about the E?

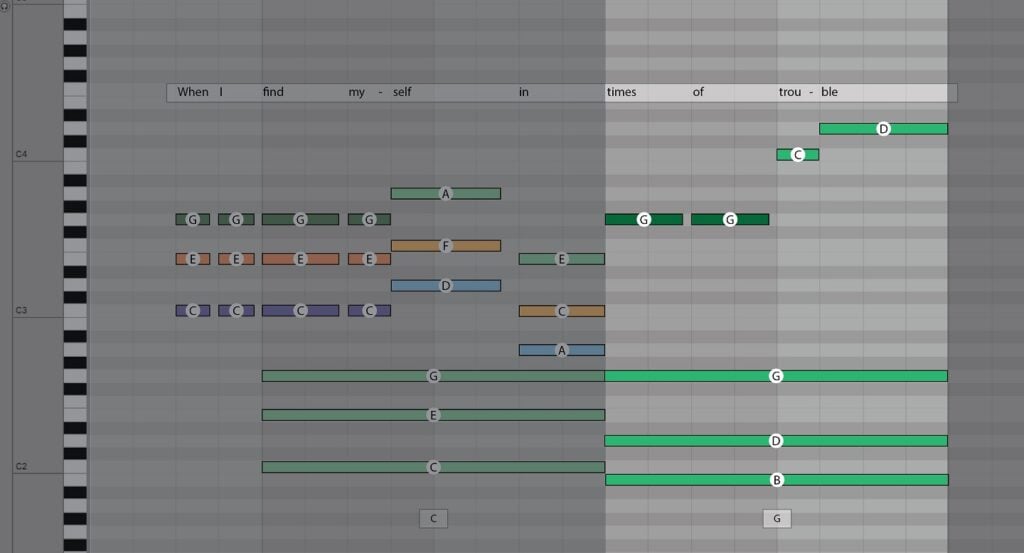

To go from G to E, we need to go down three notes on the C major scale (G is one, F is two, E is three), so we shift the whole section down by a third. Here’s what this looks like:

Note: If you’re using a MIDI workspace to help you figure out harmonies like we’re doing here, just be careful. When we talk about shifting everything up or down by a third interval, it doesn’t just mean highlighting every note and shifting it by the same amount on the piano roll. Instead, we shift every note by the same interval on a specific scale. Sometimes, the distance between two notes on a scale is two semitones, but sometimes it’s one. It’s helpful to have a MIDI controller out in front of you so you can play the scale and remind yourself what notes it contains.

The new notes are E-E-E-E-F-C. Notice that the F doesn’t belong in the C major chord, but it sounds fine because it’s a filler note. It’s in harmony with the melody, but it doesn’t interfere with the underlying chord. The Es, on the other hand, maintain their position as anchor notes. As long as they’re in harmony with the C major chord, this harmony line will work.

Using the same process, we can also shift the anchor note from G to C. This new harmony line would look like this:

This is just one option. If you take a look at the chord that’s created on the word “in”, that’s an A minor. If that E was an anchor note and we stayed on it longer, its harmony would clash with the C major chord. But, because we skip over it pretty quickly, it’s not really noticeable.

However, another option to consider is this: we can treat that E as an anchor note and try to build a C major chord with the harmonies underneath. That might sound even better, and would look something like this:

Now, notice how the orange harmony line actually ends up on a higher pitch than the green melody. This is called a voice crossing. We generally want to avoid voice crossings, especially in settings where the two lines have the same volume and place in the mix—for example, choir performances—because it can cause confusion.

But, if you’re recording a song and you plan to mix the melody and harmony differently, then this can be completely fine.

Navigating jumps and smoothing transitions (“times of trouble”)

The next section is supported by the G major chord, which includes the notes G, B, and D. The melody follows the notes G-G-C-D.

Once again, G is the anchor note. However, we can’t simply continue the same two harmony lines from the previous section, because they’re anchored to E and C, which fit the C major chord. Instead, we need to create new harmonies and anchor them to the G major chord.

Let’s try shifting G down to a D. Now, when it comes to the two filler notes C-D, the melody does quite a big jump to get there. If possible, we typically want to avoid doing jumps like this in the harmony. When harmonies are nice and close, they’re not only easier to sing, but they sound cohesive, too.

So, we need to find another place to put these two filler notes. Remember, they don’t actually need to harmonize with the G major chord—they just need to harmonize with the melody. Is there an interval we can use to shift them somewhere close to that anchor D? A third is always a great choice, and going a third up from C-D brings us to E-F. Shift that down an octave, and we’ve got the line D-D-E-F. That’s perfect!

Lastly, let’s write a harmony line that uses B as the anchor note. To get to the B, we can shift the anchor G up or down. Since the harmonies in the previous section were both lower, let’s keep these ones under the melody, as well. The goal is to make the transitions between sections as seamless as possible.

Once again, we want to avoid doing a big jump from the anchor B to the filler notes. Are there two notes that are close to the B that would also harmonize with C-D and E-F? Well, if we go a third down from C-D, we’d get A-B. Move down an octave, and that’s about as close to the anchor B as we can get!

And there you have it: two harmony lines below the melody that complement it, match the underlying chords and are easy to sing.

Access the world’s best sample library and connected creator tools for only $0.99.

Other types of vocal harmonies

When coming up with vocal harmonies, you can use music theory as a starting point to identify chord tones and intervals. But, after that, it’s just like coming up with a new melody—there’s freedom to take it anywhere, as long as it complements everything else that’s happening in the song and sounds pleasing to the ear.

In the example above, we looked at how to create parallel harmonies—they follow the shape of the melody as closely as possible. But there are other kinds, as well.

You can move in the opposite direction from the melody and create a contrary harmony. You can pick a note and stay on it, creating an oblique harmony. You can even stack the chord tones and stay on them for the entire duration of the chord. When you’re not sure what else to do, this is an easy harmony to try.

You can also mix and match techniques. For example, follow the melody for a bit, and then stay on a single note. There are really no hard rules about what your harmony can or can’t be. If it sounds good, then it works!

Trust your ear

We can look to theory to explain why certain notes sound good together, while others don’t. But, don’t feel like this is the only option. Many singers make decisions based solely on what sounds pleasing to the ear. Unless you know music theory like the back of your hand, it can sometimes be faster to try out a few different notes and go with the one that sounds best.

For example, we talked about how melodies are based on the key and scale of the song. But, most songs also have chords and notes that are borrowed from other keys or modes. When this happens, the harmony needs to deviate from the overall scale, too. Instead of spending time trying to figure out what that other scale or mode is, it’s often easier to just trust your ear and go with what sounds good.

How to find vocal harmonies: Conclusion

At first, you may need to sit with a keyboard and meticulously plan out each note of the harmony you’re going to sing, much like we did in the “Let It Be” example.

But, it won’t always be like this. With enough experience and practice, you’ll eventually be able to come up with harmonies intuitively in your head, and often on the fly!

To get there quicker, listen to as much music as you can and try to sing along with the harmony parts. If you find it difficult to sing something different than the lead vocal and tend to switch back to the melody, start with oblique harmonies—just pick a note and hold it. From there, you can experiment with gradually including other notes, as well.

If you have trouble hearing harmonies in songs, you can try listening to isolated vocal samples with harmonies. Without the fully produced track in the background, it might be easier to hear what each harmony part is doing. You can then try and replicate these samples by recording your own voice.

It won’t happen overnight, but the more you practice hearing, singing, and creating new vocal harmonies, the easier it will get. Stay the course and you’ll be a harmony whiz in no time!

Browse vocal harmonies on Splice:

March 20, 2024

.svg)

.svg)