Music theory is an ever-winding path, full of new sights to see and tools to tinker with.

Regardless of how much or how little music theory you bring into your projects, understanding the harmonic technique of parallel chords can help add new and unexpected colors to your music. Applied thoughtfully, they can create a memorable impact on your listeners, whether or not you’re working within the genres where they first gained popularity.

In this guide, we explore what parallel chords are and break down how you can use them in your music. Feel free to use the table of contents below to navigate to a specific section.

What you’ll learn:

- The fundamentals: Keys, scales, and chords

- What are parallel chords?

- Popular voicings and movement patterns

- Applying parallel chords in different genres

- How to use parallel chords in your music

Feeling ready? Let’s dive in!

The fundamentals: Keys, scales, and chords

Western music theory is built off of the idea that a key dictates the scale of a song, and therefore, what chords we technically should and shouldn’t use. With this core guideline, we can take any type of key and scale and know generally which notes to focus on and which to avoid.

The first scales we learn in music theory are the major and (natural) minor scale, often followed by the harmonic and melodic variants of the minor scale. Each of these prescribe “correct” notes for you, and any note which diverges from that is called an incidental.

But what about multiple notes or entire chords that diverge from a scale? Enter parallel chords, the fascinating harmonic tool which outright disregards a foundation of music theory.

What are parallel chords?

Parallel chords are a group of chords that share the same exact set of intervals, rather than following the expected major, minor, or diminished voicings of a given key.

The instrument can make a big difference in how unusual this might sound to a listener. A guitarist, for example, might play a G♯ major barre chord on the third fret, and then move the entire hand up two frets to play an A♯ major, and two again to play C major. The finger positions don’t change, and certain genres like pop punk and classic rock often showcase this through the use of power chords. Turn on just about any AC/DC track and you’re bound to start picking this up, but it’s a harmonic technique utilized across countless genres.

Piano players, as another example, can’t simply move up and down a fretboard with the exact same hand shape. Because maintaining a voicing on a piano requires the player to adapt to the black keys, playing a chord progression with parallel motion may take a bit more unwiring of the player’s habits.

So why exactly do we use parallel chords if they break one of the basic guidelines of music theory? Firstly, the sense of continuity is very palpable to the listener, creating a sense of comfort in the relationship between each note, even if the feeling of living within a given key is put at risk. Outside of the example of power chords (which, as a reminder, are simplified chords with just perfect fifths and the third omitted), parallel chords have become a defining element of many modern and largely electronic genres.

Popular voicings and movement patterns

Now that we know what parallel chords are, let’s break down how to build progressions using them. Parallel chords work best when the voicing itself carries strong character, and the way it’s moved is intentional. Let’s take a look at this in three components: (1) the voicing, (2) the movement (interval), and (3) the spacing.

While a standard major or minor triad can absolutely be used, parallel motion really shines when a voicing goes beyond that, with something like a seventh, for example. Try your first parallel motion progressions with any of the basic seventh chord shapes:

- Minor seventh chords (root – minor third – perfect fifth – minor seventh)

- Major seventh chords (root – major third – perfect fifth – major seventh)

- Dominant seventh chords (root – major third – perfect fifth – minor seventh)

- Minor major seventh chords (root – minor third – perfect fifth – major seventh)

From the first chord you decide to use, you can start out with a few intervals of movement:

- Whole-step movement

- Half-step movement

- Modal shifts

What are modal shifts?

The only example above that might not be obvious is modal shifts, which are also referred to as modal interchange. Quite simply, rather than relying on a consistent whole or half-step pattern, you can let the scale dictate how far each chord jumps.

To implement a modal shift, we intentionally feature the chords which are supposed to have a different voicing than our starting chord. So, if you’re starting with a major seventh chord and the song is technically in a major scale, you might jump to the ii, iii, or vi chords—but with a major voicing.

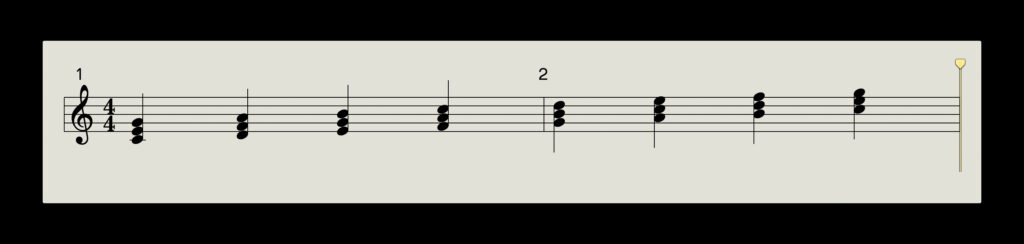

Have a listen to this and the other two, more clearly regimented types of movement:

You’ll start to notice that the movements matter just as much as the chords themselves. The largest jump (a major third) feels rather bold, perhaps too much so, while smaller steps created subtle, somewhat tense step-like motion.

Try it out in your preferred DAW, and after you’ve had your fun with some basic chords, experiment with any other voicings that you tend to use in your music. This is where you can highlight your signature coloration, whether that be through suspensions, sixth chords, or inversions. Maybe you start with a chord that sounds particularly open, closed, or spread out across a wide range of octaves. Give them all a go, and through this experimentation, you’ll improve your theory knowledge and improvisational and composition skills—and you just might uncover a new distinguishing quality for your project.

Applying parallel chords in different genres

While anyone can use this technique, parallel chords are strongly associated with Detroit techno and early electronic music genres, where producers used synthesizers to move chord shapes fluidly. Rather than following classical harmony rules, these movements focus on texture, repetition, and forward momentum.

Outside of Detroit techno, you’ll likely encounter some form of this technique in certain periods and scenes of jazz, R&B, neo soul, pop, and game music. If you know what to listen for, you’ll find your ears perking up and suspecting a use of parallel chords more often than you might think. In many ways, this is what learning any music theory concept can feel like—a little box of patterns that allows you to analyze and better understand the building blocks of a song, wherever you are.

How to use parallel chords in your music

While we’re certainly big fans of parallel chords, they can also sound repetitive if left unchanged for too long. If you’re centering this technique in a track, the key to an engaging, evolving listening experience lies in subtle variation.

With that, here are some ways that you can guide your listeners in that journey:

- Invert chords to allow the thirds, fifths, and sevenths of your chords to guide the bassline. This can allow you to smooth out your low end with more gentle movement and create a more cohesive chord progression while composing outside of a traditional key.

- Diversify your timbres to create a sense of sonic richness for the listener. By presenting them with layers of different instruments in unison, you can amplify the impact of the parallel chords while creating a more memorable experience.

- Use automation to even more intentionally control the dynamic impact. When automated cleverly, filters, reverb, panning, and delay (among many other effects) can help otherwise repetitive chords feel alive.

- Pair parallel chords with traditional progressions to intentionally bring attention to the technique. Returning to a few chords in your original key can also help ground the listener from the somewhat unsettling feeling of parallel chords, and again contributes to the idea of tension and release.

Conclusion

And there you have it! Hopefully this guide gave you some insight into the definition, sound, and possible use cases of parallel chords. Although they can feel a bit unruly at first, parallel chords are an easy and surprisingly versatile to add harmonic interest to your music.

What other music theory topics would you like to see us explore next? Start a conversation with us and an ever-growing community of music creators via the Splice Discord.

Explore royalty-free melodies, chord progressions, and grooves by key, BPM, genre, and more:

February 9, 2026

.svg)

.svg)