We all know the sound: it’s that ubiquitous crash at the end of a bar. It’s that familiar reverb-washed sample that serves as the booming signal of the next section for a big EDM tune. It’s the split-second breather from the forward momentum of the kick and bass. It’s that super-compressed snare with a gated tail that is simply too large to overlook. In the production world, it’s known as the Pryda Snare, and it’s quite possibly the most common trope in big room music. Read on to learn the history of the Pryda Snare and explore the featured project on Splice so you can learn to recreate it.

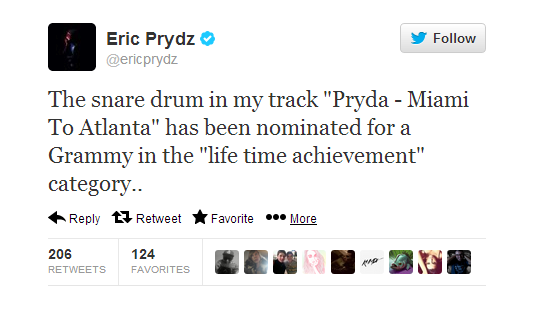

The Pryda Snare gets its name from — you guessed it — Eric Prydz. In early 2009, the Swedish producer released “Miami to Atlanta,” a song that would go on to become one of his most iconic tracks to date. Aside from its typically smooth Pryda chord progression, the track is notable for one thing: it’s creative use of the snare drum.

The song starts out like most Pryda tracks, luring you with its understated melody, but when that minute mark hits, it quickly ramps up the energy thanks to this insanely catchy snare hit. Every few seconds, the swooshing sample clears out everything in its path, creating the rhythmic syncopation that has made the track so memorable.

So what’s all the fuss? Why has one snare sample received so much attention over the years? The problem arose circa 2011-2012. As this new form of festival music came to fruition centered around distorted kick drums and triplet melodies, so too did Prydz’s snare find its way into nearly every production of this burgeoning big room genre. It wasn’t so much the way it sounded (most producers can recreate it with ease), but the way it was used.

Just as in “Miami to Atlanta,” the sample was employed as a segue into a more energetic section and then used later in the track as a break between longer 16-32 bar sections. Always, without fail, the snare would be followed by that sudden drop of silence, mimicking its exact role in Prydz’s original.

One of the earliest and most well-known examples is Swedish House Mafia and Knife Party’s late 2011 collaboration, “Antidote.” The sample serves as one of the primary elements of the track, initiating the drop and then returning every 8 bars or so. Around the same time, the snare famously appeared in R3hab & Swanky Tunes’ “Sending My Love,” Hardwell’s remix of “Hangover,” and Nicky Romero’s “Toulouse.”

From thereon, the Pryda Snare spread like wildfire, finding its way into every corner of big room music. In 2013, it became a defining feature of the trance infused variant of big room house, or “trouse” as it is often referred. The biggest purveyor of the sound, W&W, used it conspicuously in “The Code” and “D# Fat” alongside Armin van Buuren. At the same time, it was featured in nearly every festival anthem, from Dada Life’s “Born to Rage” to TJR’s “Ode to Oi.” Meanwhile, a young producer from the Netherlands would sample it in what eventually became the the track of the year. “Animals” by Martin Garrix is likely the most commonly cited example of the Pryda Snare. The song drops a minute and a half in. Sixteen bars later — like clockwork — the Pryda Snare arrives and the kick ducks out of the way for its signature crash.

The popularity of the sample eventually helped fuel a backlash against big room house in 2013 ( which continues to this day in even greater disdain). The widespread rebuke was illustrated most poignantly by Daleri’s brilliant parody, “Epic Mashleg.” In an attempt to showcase just how banal the big room sound had become, the Swedish duo combined 15 tracks from the Beatport Top 100 in a one-minute segment of blaring monotony. Quite fittingly, the Pryda Snare arrives every couple of bars to signal the next transition into the next song.

And thus we find ourselves in our current state — staring down at a history of top 10 releases all copying and recreating the same snare sample. In many ways, it recalls the history of the amen break, the drum solo which became the defining sample for drum ‘n’ bass in the 90s. The difference here being that the amen break was chopped up, manipulated, and repitched over the years to fantastic creative lengths. The Pryda snare on the otherhand has consistently been reused with little to no variation. The fact that parody site Bazzfeed was able to write a story entitled “Eric Prydz sues over 1000 EDM artists in World’s Largest Ever Copyright Lawsuit” fooling thousands of people speaks volumes alone.

At the end of the day, you know what they say, imitation is the greatest form of flattery. Eric Prydz was probably not the first artist to use such a snare, but he is the artist responsible for its popularization.

Recreating the Pryda Snare

So how does one go about making the Pryda Snare? Well of course there’s the obvious route: you can sample it directly from “Miami to Atlanta” or from any of the thousand big room tracks have transpired in its wake. But for those looking to recreate it from scratch, here’s a quick rundown. Bear in mind there are many ways to create a Pryda-styled snare. This is one of the easiest.

Step 1: Find a snappy snare with a solid low end and a distinct tail. 909 snares are a good place to start. Pitch them down a semitone or two to get more body and low end.

Step 2: Apply a standard reverb with a 3-4 second decay time and 50% wet.

Step 3: Apply a compressor with a low threshold (around -25dB), slow attack (around 75ms), and medium release (around 175ms). Bring up the output volume to taste.

Step 4 (optional): Apply a saturator with soft clipping turned on and increase drive to taste for extra emphasis.

Step 5. Resample the processed snare and cut off the tail of the new sample at the desired length.

Explore royalty-free one-shots, loops, FX, MIDI, and presets from leading artists, producers, and sound designers:

September 23, 2014