Illustration: Lan Truong

Harmony not only helps us identify what notes sound good together, but why they sound good together.

It also plays a pivotal role in helping us tell a story with our music. But exactly what is harmony in music—a term that’s used to describe so many different things—and what are the building blocks that constitute it? In this article, let’s define what harmony is and go over important subtopics that pertain to harmony such as intervals, triads, chord progressions, and more.

See the table of contents below to easily jump to a specific section:

What you’ll learn:

- The definition of harmony in music

- What are chords?

- What are triads?

- What are chord progressions?

- How to create chord progressions

Feeling ready? Let’s dive in!

What is harmony in music?

Put simply, harmony refers to the simultaneous sounding of different musical notes. We hear harmony in almost all of the music that we listen to. In many songs, instruments like piano or guitar are used to outline the harmony—the piano in The Beatles’ “Let It Be,” for example, defines the harmonic structure of the song while serving as a nice musical bed for Paul McCartney’s vocals:

Other songs directly intertwine harmony with the main melody—Imogen Heap’s “Hide and Seek,” for example, is characterized by its colorful use of vocal harmonies:

Even though there’s a clear main melody, the supporting vocal harmonies really help add interest and emotion to the song. How do The Beatles, Imogen Heap, and others craft these sort of supporting layers that add so much to their music? Below, we’ll dive into core concepts that help us create our own harmonies.

What are chords?

A chord is a collection of pitches that form a single harmonic idea, and serves as the foundation of harmony in music. While you don’t need to be a veteran musician to be familiar with the difference between individual notes and chords, let’s take a quick listen to make sure we’re on the same page.

Example 1: Individual notes going up the C major scale

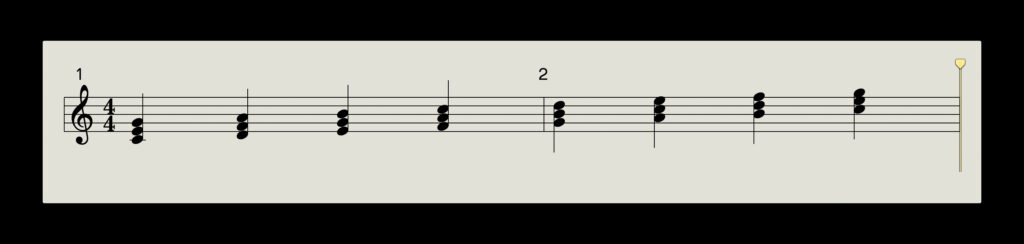

Example 2: A series of chords built off of the C major scale

Note how the chords in the above sequence don’t sound random—they make sense and sound musically pleasant, both on their own and in relation to one another. Let’s define what these chords are, and figure out how we crafted them from a music theory perspective.

What are triads?

All of the chords heard in Example 2 are triads, which are three-note chords that consist of two stacked thirds (an interval created by pitches that are two letters apart, with or without accidentals: C and E, D and F♯, G and B♭, etc.). If stacked in this way, the interval between the root (the lowest pitch) and the fifth (the highest pitch) is a fifth (ex. C and G, C♯ and G♯, D and A, etc.). Following this idea, the middle pitch is called the third, simply because it’s a third above the root.

If the root is the lowest pitch of the chord, we say that the triad is in root position. Let’s take a look at how root position triads appear visually:

You can easily recognize root position triads on the staff because they’ll occupy either three consecutive lines or three consecutive spaces

The same series of root position triads, expressed on the piano roll

How to create triads in a key

The sheet music and piano roll images above are a transcription of the ascending chords from Example 2. In order to construct each chord, we simply created triads using each note in the C major scale as the root, while making sure that every pitch (the root, the third, and the fifth) in the chord belonged to the key of C.

For example, when building a triad off of the note C, we stacked an E and a G over it, because that would allow for us to create two stacked thirds without using any notes that don’t belong to the C major scale (like E♭ or G♯). We then moved on to D, stacking an F and an A over it, and then stacked a G and a B over E, etc.

Your turn: In the key of C, the triad that uses G as the root note will consist of the following third and fifth:

A. A and B

B. B and D

C. D and F

Answer: B

We used the accidental-free key of C as our example for convenience, but this same process can be applied to build the entire collection of triads that naturally belong in any key. And no matter what major scale we choose, we’ll find that we get a similar-sounding collection of chords:

Example 3: The collection of chords that belong to the key of D major

Example 4: The collection of chords that belong to the key of G major

Example 5: The collection of chords that belong to the key of E♭ major

The reason why these sequences sound similar regardless of the key is because each chord’s triad type, or quality, remains consistent. The two most common qualities are major triads and minor triads. To understand these, we need to be able to first differentiate between major thirds and minor thirds.

What are major and minor thirds?

That’s right—not all thirds are the same! Major thirds are thirds that are specifically four semitones (half steps) apart. For example, the interval between C and E is a major third because they’re two letters apart, and it takes four semitones to get from C to E: C♯ (a.k.a. D♭) → D → D♯ (a.k.a. E♭) → E.

Here’s what a major third sounds like:

On the other hand, minor thirds are thirds that are just three semitones apart. For example, the interval between A and C is a minor third because they’re two letters apart, and it takes just three semitones to get from A to C: A♯ (a.k.a. B♭) → B → C.

Here’s what a minor third sounds like:

Like major and minor scales, the major third interval is commonly perceived as being ‘bright’ and ‘happy,’ while the minor third is more commonly viewed as being ‘dark’ and ‘sad’ (that said, context is everything when it comes to their emotional quality in practice).

Your turn: Are the following intervals major thirds or minor thirds?

1. D and F#

2. B and D

3. C# and E

4. A and C#

1.

2.

3.

4.

Chord qualities in major keys

Now that we have an understanding of major and minor thirds, let’s go back to the topic of major and minor triads. Simply put, in major triads, the third is major, and in minor triads, the third is minor.

Here’s how a major triad sounds:

And here’s how a minor triad sounds:

As we heard in Examples 3 – 5, even if we change keys, the chord quality will always be the same for chords built off a particular scale degree (the numbered position of a pitch in a scale) in the major scale:

The chord qualities of each scale degree, using the C major scale as an example

You may notice that there’s one triad in the image above that’s not major or minor in quality, but diminished. In all of the other triads, the fifths are by default perfect fifths, meaning they’re exactly seven semitones above the root. However, a diminished triad is made up of two stacked minor thirds, meaning the fifth is actually a diminished fifth, only six semitones above the root.

This seemingly small change of just one half step creates a sound that’s quite tense—take a listen:

That said, don’t worry too much about the diminished triad for now, since its dissonant sound keeps it from being used as often as the other chords, especially in popular music. Speaking of which, let’s finally dive into how we can actually use our collection of chords to make some music.

What are chord progressions?

A chord progression is a succession of chords that serves as the harmonic backbone to a piece of music. If you listen again to the piano in “Let It Be,” you’ll hear that it repeats a handful of chords over and over. The resulting chord progression sounds quite pleasant, definitely more than our chord scale in Example 2 (which doesn’t sound bad—it’s just not quite a timeless classic like “Let It Be”).

While our exercise outlined all of the chords that naturally belong to a key, how did The Beatles choose which few chords to use, and how to order them?

Roman numerals

What’s key to understand when it comes to building chord progressions is the idea that chords built on different scale degrees serve different functions. That is to say, a C major triad may play an entirely different role in the key of C major than it does in the key of F major, despite the fact that it can be found in both keys.

In the previous image outlining scale degree triads, you’ll see we also labeled each triad with a roman numeral (I, ii, iii, etc.), with the casing corresponding to whether the chord’s quality is major or minor. These labels tells us about how each chord belongs and behaves in our key, and for this reason we generally like to use them when talking about chord progressions.

How to create chord progressions

Now, as we implied with our discussion of the diminished vii° chord, there are some chords that are seen more commonly in popular music than others. Specifically, the I, IV, V, and vi chords get a lot of love. In fact, countless pop songs rely on just looping some order of these—it’s almost kind of funny how many iconic tracks share the same harmonic structure, as highlighted in this medley of songs that feature the I – V – vi – IV progression (which includes “Let It Be”):

This particular progression is especially common because the way the chords flow into one another aligns really well with their natural tendencies. We’ve outlined some of these said tendencies below, for you to consider when building your own progressions.

Harmony tips for writing chord progressions:

- If we want our progression to have a major sound, the I chord will typically serve as the ‘home base,’ making it a common choice as the first chord in the progression.

- If we want our progression to have a minor sound, the vi chord will typically serve as the ‘home base,’ making it a common choice as the first chord in the progression.

- The IV chord often leads smoothly into the V chord, but it can also be used quite flexibly, often starting and ending progressions as well.

- While it’s rarely a chord that we start our progression on, the V chord often leads smoothly into the I and vi chords.

There are some deeper theory-based reasons that explain why the above statements on harmony are true, but we’ll save that discussion for a different day. For now, just note that these are tendencies, and not rules—don’t be afraid to experiment or incorporate some of the other options that we outlined earlier like the ii, iii, and vii° chords.

Writing a chord progression to a melody

While experimentation can always yield cool results, you can also get quite strategic with your progression-building. For example, if you already have a melody, think about the pitches that are emphasized in different moments. If a chord that includes those key pitches is paired with the melody, things will typically sound smoother, and if the chord doesn’t include those pitches, it can add some tension to the music. Both routes can be tasteful depending on what you’re trying to achieve.

Harmonic rhythm

Also consider playing around with the harmonic rhythm, or when and how often you change chords. While having one chord per measure is often ‘the default,’ consider speeding up or slowing down the rate at which the chords change, and listen to how that impacts the music.

What are inversions?

One last thing to consider is inverting the triad, or putting a note that isn’t the root as the lowest note. Inversions can create a smoother overall sound by minimizing any big jumps in pitch between adjacent chords.

The video above repeats the vi – IV – I – V chord progression twice. The first time, all of the chords are in root position, while the second time, the middle chords are inverted; the root is shifted up an octave in the IV chord, and the fifth is shifted down an octave in the I chord (recall how octaves don’t change the core identity of a pitch from our discussion of octave equivalence in our introduction to melody). Notice how the transitions from chord to chord sound more abrupt in the all-root-position sequence, while the transitions are little more seamless in the latter half.

This isn’t to say that the smoother feel is inherently superior, as it may again come down to taste and context. Additionally, while they don’t transform the larger function of the chord, inversions do affect emotional nuance, so that’s also a factor to consider when making these sorts of decisions.

So, what is harmony? | Wrapping up

From learning about the building blocks of triads to discussing how to sequence entire chord progressions, it would be an understatement to say that we learned a lot about the world of harmony today.

And even so, we’ve only scratched the surface; there are extended chords that add even more character to triads, ways to borrow chords from outside the key, and countless other techniques for adding harmonic color to our music. We’ll cover these topics another time, but for now, we encourage you to play around with ordering and re-ordering chords, looking up the progressions to your favorite songs, and just enjoying dipping your toes into the vast but exciting world of harmony.

If you’re reading this article as part of your journey towards creating your first track, go back to the curriculum that corresponds with your DAW and proceed to the next step:

February 1, 2023